This is the fourth of a series of 10 posts.

All 10 posts ran on consecutive weeks.

As of Labor Day, 2018, all ten of these #Teaching Tip posts are searchable on my blog.

If you're not a teacher and you're reading this,

let a teacher know they are available.

let a teacher know they are available.

I've been in enough in-service/professional-development sessions to guarantee that the information in this series is better than most of the information you’ll get while sitting through all your teacher workshops this coming school year.

You might be asking yourself,

What gives this guy the nerve to offer ideas about teaching AND commentary on professional development to anyone?

That's a legitimate question.

I invite you to follow this link and check my credentials.

This blog addresses a situation that is common to all teachers whose curriculum includes advanced topics. The process I’ll describe will work with any level of content. I used this method most often in AP Biology because I used other methods described in these blogs in all my classes

It is difficult to know how well students understand advanced concepts. Many students in AP and similar courses are excellent test takers. An “A” on an exam on a topic demonstrates a high level of “book knowledge,” in all cases. The level of understanding is more difficult to measure by traditional testing methodology.

To address the “understanding” component, I have students do a variety of creative activities. I use analogies and have students generate their own. They solve a mystery when discussing DNA. They draw “portraits” of family members after a genetics simulation. I addition, are various times my students have, among other things,

· Written letters to the developer of the microscope and

· Written letters from their brain to their lungs attempting to get the human to stop smoking.

· Written dialogs between them and a deceased friend who died of drug use where the deceased friend warns them of the dangers of drug usage.

· Written journal entries chronicling the development of a bird embryo.

· Written poetry to highlight environmental issues.

· Drawn comic strips illustrating different invertebrates.

· Drawn/Digitally produced comic books and graphic novels on how rocks form.

· Drawn or painted original art highlighting endangered species.

The assignment highlighted in this blog is The Voyage of Uli Urea. Students describe filtration and urine production in the kidney in a story.

The Voyage of Uli Urea

Your excretory system does a magnificent job of removing some very nasty waste materials from your bodies. You hardly ever think about this system. BUT, you might if you had finished a L-A-R-G-E soft drink about an hour ago and you were sitting on the wonderful seat of a yellow school bus and you were bouncing along on a rough stretch of roadway and the mean, rotten bus driver would not stop and take a "potty break."

Anyway, you are to pretend to be "Uli Urea," a molecule of nitrogen waste in the blood of your body. Use the words listed below in a cute story that describes the excretory process.

To come anywhere close to full credit on this assignment, you will have to use information from your Campbell text. Other sources are, of course, okay, but if you use anything but Campbell, you must reference your information. In addition, you have to explain what happens in the Loop of Henle (both down and up)—you’ll need to use terms like hypertonic, hypotonic, permeable, impermeable for any hope at full credit.

The first time you write one of the words from this list in your story it must be in ALL CAPITAL LETTERS and UNDERLINED. Example: KIDNEY. The words must be used in correct order that they occur in the excretory process or you will lose points.

WORD LIST:

AQUAPORIN

|

PROXIMAL TUBULE*

|

ACTIVE TRANSPORT

|

RENAL ARTERY*

|

BOWMAN'S CAPSULE*

|

RENAL ARTERIOLE*

|

COLLECTING TUBULE (DUCT)*

|

SALTS

|

DISTAL TUBULE*

|

TOILET

|

FILTRATION

|

UREA

|

GLOMERULUS*

|

URETER*

|

HOMEOSTASIS

|

URETHRA*

|

KIDNEY

|

URINARY BLADDER*

|

KIDNEY PELVIS*

|

URINATION

|

LOOP OF HENLE*

|

URINE

|

NEPHRON

|

WATER

|

The terms marked with asterisks (*), must be in the correct anatomical order.

Your final draft should be word-processed using as many pages as necessary. You will be allowed one error in spelling or grammar per page of text you write. After that first error, points will be deducted for each additional mistake.

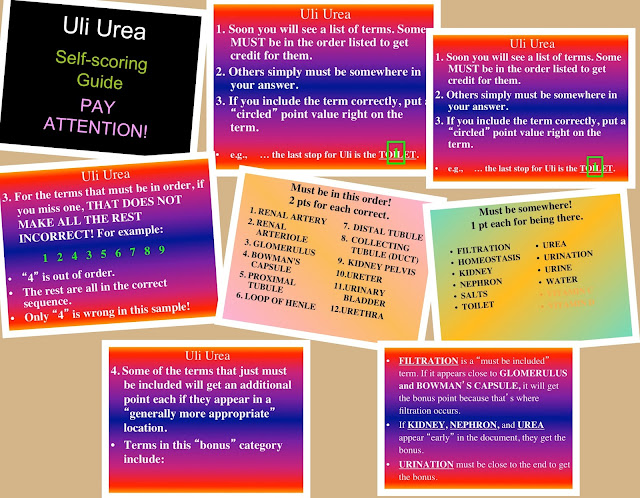

Once the stories are complete, students “trade and grade” papers using the PPT slides shown below.

The graders use pens or pencils I provide. Three times during the process—after slide 5, after slide 6, and at the end, they record partial scores in the margin. They total those scores. See the sample below.

After this process, I had only to read the papers for coherence/content, adjust an occasional grading error by the student grader, and deduct points for grammar if there is more than one mistake per page. More often than not, any grade adjustment ends up in favor of the author of the paper. It takes relatively little time for me to do my part of the grading. All the grunt work was done during the peer grading session.

Students like knowing how they did on what was graded before class ends. Because my time commitment is reduced, they get their final grades quickly as well.

In addition, I have a clearer picture of the level of understanding of students on this concept, which will be on their unit exam, than if I asked them to "draw and label a nephron and describe each label in one sentence."

An Aside:

Kids tend to be brutal sticklers to what I say or show when grading. For example, if I say, “there should be twelve items in these two paragraphs,” it’s not uncommon for a hand to shoot up. “This paper has eleven in two paragraphs and one in another. I gave them eleven.”

When that happens, or if I adjust while reading the paper, I—the teacher—come across as a helper, not an executioner. “Thank you for the extra point,” is common. For an example of how little most students understand how their grade in the class is calculated, keep coming back to this blog.

Email me: EIT.DrD@gmail.com with questions/comments.

Or, if you'd like more information or samples of anything described in this series, send an email there!

#TipsForTeachers. Thoughts on Grading delves into group work and study guides.

SEO: Teaching, teachers, grading, homework, reading assignments

Follow me on

Twitter: @CRDowningAuthor

I'd appreciate your feedback!

No comments:

Post a Comment