|

| The original of this blog post was revised in 2018. |

In the first blog on this topic, I explained that my definition being a “successful writer” has changed in the nearly four years I’ve been writing professionally. To review, here are the first three iterations.

My first definition of success was “get published.”

My second definition of success was “make money.”

My third definition of success was “getting books out.”

My fourth definition of success was “be patient, Grasshopper.”

The third definition of success refers to the frenzied publishing schedule I fell victim to. I know now that patient working with a book is a sign my maturation as an author.

There is no excuse or reason for publishing a book that is littered with errors in grammar, spelling, or sentence structure.

There are ways to reduce the number of those types of errors without significant financial outlay. As stand-alone options, they each have value. Used collectively, these options have more value than the sum of the individual methods.

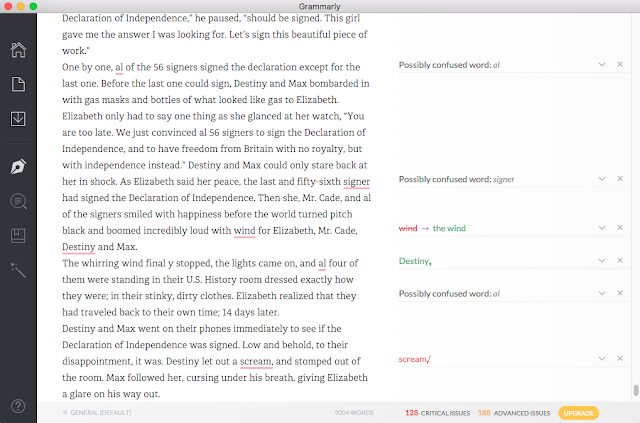

Grammarly.

I use only the free version. This does a good job at pointing out certain types of grammar issues, including most common comma errors. Grammarly was revised in early 2018. The free version finds fewer types of mistakes. While it is now less valuable than when I began using it, Grammarly is still a good place to start checking for errors.

I use only the free version. This does a good job at pointing out certain types of grammar issues, including most common comma errors. Grammarly was revised in early 2018. The free version finds fewer types of mistakes. While it is now less valuable than when I began using it, Grammarly is still a good place to start checking for errors.

Grammarly does not use the same algorithm that MSWord uses for grammar. You have to decide which of the experts you want to use for direction. Whether you use Grammarly’s grammar rules or MSWord’s rules, there will be types of grammar not checked, particularly the current free version of Grammarly.

This is a powerful tool. However, unless you subscribe, you have a 500-word limit to what you can check. This has an annual or multiyear fee including a lifetime offer.

|

| This is part of the summary report offered. It scrolls down several screens. You can have it emailed to you. |

|

| The Grammar Check screen. Each icon in the top menu bar produces a report. |

The newest version (3.0.2 at the time of posting) of this inexpensive (currently $19.95 one-time cost that includes desktop use) software provides feedback in dramatic fashion. It uses various colors to highlight issues in your manuscript.

|

| A screenshot of Hemingway. It's obvious where you need to consider your phraseology and sentence construction. |

While these are valuable sources of information, all of them remove the formatting of your text. If you copy/paste or open a saved version of any of these, you have to reformat the text.

Experiment.

I find it easiest to keep my original open and make the corrects in it rather than in the Grammarly or Hemingway file. The ProWritingAid copy/paste is the closest to what I uploaded.

Experiment.

I find it easiest to keep my original open and make the corrects in it rather than in the Grammarly or Hemingway file. The ProWritingAid copy/paste is the closest to what I uploaded.

Visual “tricks.”

Near the end of my editing process, I use two features of Word in tandem. These work because your brain’s preset for reading is black print on white paper with letters of a size regularly used in documents or books. Both tricks that follow are different enough from the norm that your brain focuses more tightly what you are reading.

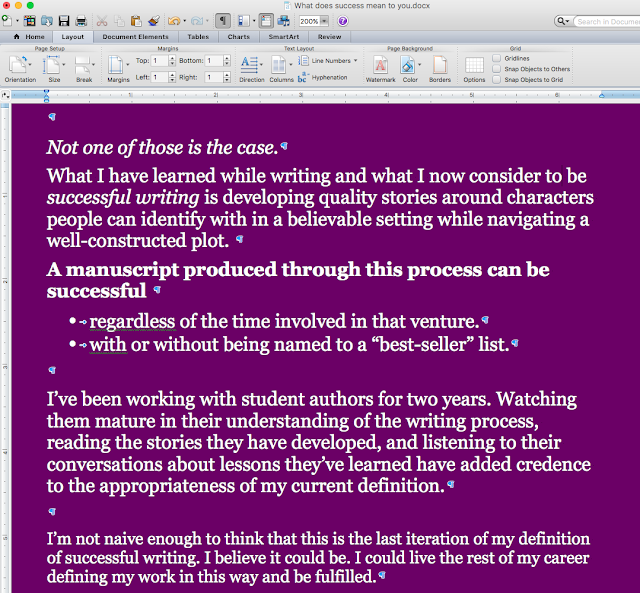

First I color the background of my manuscript before editing.

This is a simple process. It’s not permanent, and the color does not print. It forces your brain to see the words differently than the normal black print on the white background you use while writing. Some background colors leave the print black. Others—dark blue, purple, and black—generate your text in white. When your brain is working outside the “norm,” it will see mistakes you’ve missed up to that time. Ultimately, more errors are found and you have a better piece of work

Second, I zoom the size of the file on my screen to at least 200%.

The oversized print forces your brain to interpret the words in a different manner—more errors are found.

For maximum benefit, switch colors and zoom levels periodically. Remember, your brain will pay closer attention to what it perceives as a new form of data—more errors are found.

Final recommendation

WAIT

You wrote your story. Each word in the story was your idea. Your brain is a jealous and lazy organ. It inherently wants to keep what it thought up and delivered to your story in the first draft. It’s not good at pointing out all errors in a manuscript you wrote.

After you’ve done all the above, close the file.

Don’t look at it again for at least one week.

Two weeks without looking is better.

Three or more weeks is not too long to wait until you read through the manuscript again.

By giving your brain a break from the routine of editing, when you revisit the work, your brain is much less vested in the content. I suspect you will be shocked—or at least surprised—by the number of wrong words, punctuation errors, and sentence issues you find.

Used alone, none of these options—Grammarly à font size—is sufficient for preparing a novel-length manuscript for publication. Even if used collectively, these options are insufficient for preparing a novel-length manuscript for publication. However, each of the above is a separate edit and adds time to your writing process. “Be patient, Grasshopper.”

“Be patient, Grasshopper.”

Take time to wait until you can afford some level of professional editing or proofreading.

“Be patient, Grasshopper.”

Ask around.

Find an editor or proofreader that has good relationships with several authors.

“Be patient, Grasshopper.”

Establish a timeline that allows you to use the professional without stressing you or badgering the editor/proofreader.

My current definition of success is being able to “do what you do because you like what you’re doing.”

This sounds like

· I’ve turned my back on fame and fortune.

· I’ve turned my back on fortune.

· I’ve turned my back on productivity.

· I’ve turned my back on goals and deadlines.

Not one of those is the case.

What I learned while writing and what I now consider to be successful writing is developing quality stories around characters people can identify with in a believable setting while navigating a well-constructed plot.

A manuscript produced through this process can be successful

· because the time involved in that venture led to a quality end product.

· with or without being named to a “best-seller” list.

I worked with student authors for three years. Watching them mature in their understanding of the writing process, reading the stories they developed, and listening to their conversations about lessons they’ve learned have added credence to the validity of my current definition.

I’m not naive enough to think that this is the last iteration of my definition of successful writing.

I believe it could be.

I could live the rest of my career and define my work in this way and be fulfilled.

Four years ago, I never considered any definition of writing success except “get published.”

I am grateful that my outlook has matured.

I will Review: ProWritingAid in early 2019.

Follow me on Twitter: @CRDowningAuthor and Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CRDowningAuthor